Flag Day: The Case For Reviving Flag Protection Laws

Texas v. Johnson (1989)

In the landmark case Texas v. Johnson (1989), the center left Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that the act of burning an American Flag is protected free speech.

Even more infuriating is that the case was brought forth by Gregory Johnson, a 20-something member of the Communist Youth Brigade, who was convicted of burning and desecration of the American Flag in violation of Texas law. The offense happened outside the 1984 GOP Convention in Dallas, Texas as Johnson protested Ronald Reagan, Reagan’s administration, the GOP, and the USA. This stellar young U.S. citizen had also stolen the flag from down the street.

Now in his 60’s, Mr. Johnson still careens through life invigorated by his 15-minutes of Commie fame, spreading the message of hate, anti-Americanism, and of course, burning the American flag. And we only thought William Faulkner dreamed up loathsome characters like Albert Snopes—those resentful of their pitiful place in life, those having a burning resentment that causes them to strike out at any and all forces that are perceived as a threat.

As a side note…

Isn’t it ironic that a Communist brought a free speech case before the Supreme Court. Citizens, or should we say subjects, of communist countries do not have the liberty of free speech. Any person caught burning the flag of their Communist country would be summarily executed.

Equally ironic, almost all religious freedom or establishment of religion cases have been brought by atheists. Atheists inherently possess a penchant to steal, kill, and destroy (John 10:10). These cases were brought largely to remove Christian religion from the public square, i.e. prayer from school, a 100-year old cross from a park, a Nativity Scene from a shopping mall, etc. Ninety-nine percent of the time the atheist had just moved to the town and 100% of the time was the only person whining. Ironic? Or planned?

Prayer:

Let’s pray for Mr. Johnson. And for all Communists and Marxists in America. Ask God to bless them with discernment, knowledge, critical thinking, an animately, existent conscience, and any condition necessary for free thought. Indoctrination is the most tyrannical of all slave masters because it removes a person’s freedom to think.

Silver Lining Or Gleaming White Stripes From Texas v. Johnson

Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote the dissenting opinion in Texas v. Johnson. He bequeathed to us a sound argument describing why desecration of a flag is not free speech. He discusses the history of the American flag, the role it has played in the nation’s history, and even includes a poem. He makes the case that our flag, a symbol of our nation, has a unique place in American history, and should not be relegated to the whims of indoctrinated malcontents with mommy issues (actually I added that last part). Constitutionally, other avenues of speech—both verbal and expressive—were available to Mr. Snopes to share his opinion with anyone who cared.

Justice John Paul Stevens also wrote a dissent in which he argues forcefully for the intangible dimension of the flag that place it outside the parameters of free speech.

Below are Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justice John Paul Stevens’ dissents in full. For this post, links and page numbers have been removed for ease of reading. Access the full ruling here complete with links and page numbers.

Context: The Makeup Of The Center Left Supreme Court That Decided Texas v. Johnson

- William Brennan, nominated by Dwight D. Eisenhower

- Thurgood Marshall, nominated by Lyndon B. Johnson

- Harry Blackmun, nominated by Richard Nixon

- Antonin Scalia, nominated by Ronald Reagan

- Anthony Kennedy, nominated by Ronald Reagan

- Chief Justice William Rehnquist, nominated by Ronald Reagan

- Byron White, nominated by John F. Kennedy

- Sandra Day O’Connor, nominated by Ronald Reagan

- John Paul Stevens, nominated by Gerald Ford

Texas v. Johnson 1989 Dissenting Opinions

CHIEF JUSTICE REHNQUIST, with whom JUSTICE WHITE and JUSTICE O’CONNOR join, dissenting.

In holding this Texas statute unconstitutional, the Court ignores Justice Holmes’ familiar aphorism that “a page of history is worth a volume of logic.” New York Trust Co. v. Eisner, 256 U. S. 345, 256 U. S. 349 (1921). For more than 200 years, the American flag has occupied a unique position as the symbol of our Nation, a uniqueness that justifies a governmental prohibition against flag burning in the way respondent Johnson did here.

At the time of the American Revolution, the flag served to unify the Thirteen Colonies at home while obtaining recognition of national sovereignty abroad. Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Concord Hymn describes the first skirmishes of the Revolutionary War in these lines:

“By the rude bridge that arched the flood”

“Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled,”

“Here once the embattled farmers stood”

“And fired the shot heard round the world.”

During that time, there were many colonial and regimental flags, adorned with such symbols as pine trees, beavers, anchors, and rattlesnakes, bearing slogans such as “Liberty or Death,” “Hope,” “An Appeal to Heaven,” and “Don’t Tread on Me.” The first distinctive flag of the Colonies was the “Grand Union Flag” — with 13 stripes and a British flag in the left corner — which was flown for the first time on January 2, 1776, by troops of the Continental Army around Boston. By June 14, 1777, after we declared our independence from England, the Continental Congress resolved:

“That the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white: that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.”

8 Journal of the Continental Congress 1774-1789, p. 464 (W. Ford ed.1907). One immediate result of the flag’s adoption was that American vessels harassing British shipping sailed under an authorized national flag. Without such a flag, the British could treat captured seamen as pirates and hang them summarily; with a national flag, such seamen were treated as prisoners of war.

During the War of 1812, British naval forces sailed up Chesapeake Bay and marched overland to sack and burn the city of Washington. They then sailed up the Patapsco River to invest the city of Baltimore, but to do so it was first necessary to reduce Fort McHenry in Baltimore Harbor. Francis Scott Key, a Washington lawyer, had been granted permission by the British to board one of their warships to negotiate the release of an American who had been taken prisoner. That night, waiting anxiously on the British ship, Key watched the British fleet firing on Fort McHenry. Finally, at daybreak, he saw the fort’s American flag still flying; the British attack had failed. Intensely moved, he began to scribble on the back of an envelope the poem that became our national anthem:

“O say can you see by the dawn’s early light”

“What so proudly we hail’d at the twilight’s last gleaming,”

“Whose broad stripes & bright stars through the perilous fight”

“O’er the ramparts we watch’d, were so gallantly streaming?”

“And the rocket’s red glare, the bomb bursting in air,”

“Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there,”

“O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave”

“O’er the land of the free & the home of the brave?”

The American flag played a central role in our Nation’s most tragic conflict, when the North fought against the South. The lowering of the American flag at Fort Sumter was viewed as the start of the war. G. Preble, History of the Flag of the United States of America 453 (1880). The Southern States, to formalize their separation from the Union, adopted the “Stars and Bars” of the Confederacy. The Union troops marched to the sound of “Yes We’ll Rally Round The Flag Boys, We’ll Rally Once Again.” President Abraham Lincoln refused proposals to remove from the American flag the stars representing the rebel States, because he considered the conflict not a war between two nations, but an attack by 11 States against the National Government. Id. at 411. By war’s end, the American flag again flew over “an indestructible union, composed of indestructible states.” TeXas v. White, 7 Wall. 700, 74 U. S. 725 (1869).

One of the great stories of the Civil War is told in John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem, “Barbara Frietchie”:

Up from the meadows rich with corn,

Clear in the cool September morn,

The clustered spires of Frederick stand

Green-walled by the hills of Maryland.Round about them orchards sweep,

Apple- and peach-tree fruited deep,

Fair as a garden of the Lord

To the eyes of the famished rebel horde,On that pleasant morn of the early fall

When Lee marched over the mountain wall, —

Over the mountains winding down,

Horse and foot, into Frederick town.Forty flags with their silver stars,

Forty flags with their crimson bars,

Flapped in the morning wind: the sun

Of noon looked down, and saw not one.Up rose old Barbara Frietchie then,

Bowed with her four-score years and ten;

Bravest of all in Frederick town,

She took up the flag the men hauled down;In her attic-window the staff she set,

To show that one heart was loyal yet.

Up the street came the rebel tread,

Stonewall Jackson riding ahead.Under his slouched hat left and right

He glanced: the old flag met his sight.

“Halt!” — the dust-brown ranks stood fast.

“Fire!” — out blazed the rifle-blastIt shivered the window, pane and sash;

It rent the banner with seam and gash.

Quick, as it fell, from the broken staff

Dame Barbara snatched the silken scarf;

She leaned far out on the window-sill,

And shook it forth with a royal will.

“Shoot, if you must, this old gray head,

But spare your country’s flag,” she said.A shade of sadness, a blush of shame,

Over the face of the leader came;

The nobler nature within him stirred

To life at that woman’s deed and word:“Who touches a hair of yon gray head

Dies like a dog! March on!” he said.

All day long through Frederick street

Sounded the tread of marching feet:All day long that free flag tost

Over the heads of the rebel host.

Ever its torn folds rose and fell

On the loyal winds that loved it well;And through the hill-gaps sunset light

Shone over it with a warm good-night.

Barbara Frietchie’s work is o’er,

And the Rebel rides on his raids no more.Honor to her! and let a tear

Fall, for her sake, on Stonewall’s bier.

Over Barbara Frietchie’s grave,

Flag of Freedom and Union, wave!Peace and order and beauty draw

Round thy symbol of light and law;

And ever the stars above look down

On thy stars below in Frederick town!

In the First and Second World Wars, thousands of our countrymen died on foreign soil fighting for the American cause. At Iwo Jima in the Second World War, United States Marines fought hand to hand against thousands of Japanese. By the time the Marines reached the top of Mount Suribachi, they raised a piece of pipe upright and from one end fluttered a flag. That ascent had cost nearly 6,000 American lives. The Iwo Jima Memorial in Arlington National Cemetery memorializes that event. President Franklin Roosevelt authorized the use of the flag on labels, packages, cartons, and containers intended for export as lend-lease aid, in order to inform people in other countries of the United States’ assistance. Presidential Proclamation No. 2605, 58 Stat. 1126.

During the Korean War, the successful amphibious landing of American troops at Inchon was marked by the raising of an American flag within an hour of the event. Impetus for the enactment of the Federal Flag Desecration Statute in 1967 came from the impact of flag burnings in the United States on troop morale in Vietnam. Representative L. Mendel Rivers, then Chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, testified that

“The burning of the flag . . . has caused my mail to increase 100 percent from the boys in Vietnam, writing me and asking me what is going on in America.”

Desecration of the Flag, Hearings on H.R. 271 before Subcommittee No. 4 of the House Committee on the Judiciary, 90th Cong., 1st Sess., 189 (1967). Representative Charles Wiggins stated:

“The public act of desecration of our flag tends to undermine the morale of American troops. That this finding is true can be attested by many Members who have received correspondence from servicemen expressing their shock and disgust of such conduct.” 113 Cong.Rec. 16459 (1967).

The flag symbolizes the Nation in peace as well as in war. It signifies our national presence on battleships, airplanes, military installations, and public buildings from the United States Capitol to the thousands of county courthouses and city halls throughout the country. Two flags are prominently placed in our courtroom. Countless flags are placed by the graves of loved ones each year on what was first called Decoration Day, and is now called Memorial Day. The flag is traditionally placed on the casket of deceased members of the Armed Forces, and it is later given to the deceased’s family. 10 U.S.C. §§ 1481, 1482. Congress has provided that the flag be flown at half-staff upon the death of the President, Vice President, and other government officials “as a mark of respect to their memory.” 36 U.S.C. § 175(m). The flag identifies United States merchant ships, 22 U.S.C. § 454, and “[t]he laws of the Union protect our commerce wherever the flag of the country may float.” United States v. Guthrie, 17 How. 284, 309 (1855).

No other American symbol has been as universally honored as the flag. In 1931, Congress declared “The Star-Spangled Banner” to be our national anthem. 36 U.S.C. § 170. In 1949, Congress declared June 14th to be Flag Day. § 157. In 1987, John Philip Sousa’s “The Stars and Stripes Forever” was designated as the national march. Pub.L. 101-186, 101 Stat. 1286. Congress has also established “The Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag” and the manner of its deliverance. 36 U.S.C. § 172. The flag has appeared as the principal symbol on approximately 33 United States postal stamps and in the design of at least 43 more, more times than any other symbol. United States Postal Service, Definitive Mint Set 15 (1988).

Both Congress and the States have enacted numerous laws regulating misuse of the American flag. Until 1967, Congress left the regulation of misuse of the flag up to the States. Now, however, Title 18 U.S.C. § 700(a) provides that:

“Whoever knowingly casts contempt upon any flag of the United States by publicly mutilating, defacing, defiling, burning, or trampling upon it shall be fined not more than $1,000 or imprisoned for not more than one year, or both.”

Congress has also prescribed, inter alia, detailed rules for the design of the flag, 4 U.S.C. § 1, the time and occasion of flag’s display, 36 U.S.C. § 174, the position and manner of its display, § 175, respect for the flag, § 176, and conduct during hoisting, lowering, and passing of the flag, § 177. With the exception of Alaska and Wyoming, all of the States now have statutes prohibiting the burning of the flag. [Footnote 2/1] Most of the state statutes are patterned after the Uniform Flag Act of 1917, which in § 3 provides:

“No person shall publicly mutilate, deface, defile, defy, trample upon, or by word or act cast contempt upon any such flag, standard, color, ensign or shield.”

Proceedings of National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws 323-324 (1917). Most were passed by the States at about the time of World War I. Rosenblatt, Flag Desecration Statutes: History and Analysis, 1972 Wash.U.L.Q.193, 197.

The American flag, then, throughout more than 200 years of our history, has come to be the visible symbol embodying our Nation. It does not represent the views of any particular political party, and it does not represent any particular political philosophy. The flag is not simply another “idea” or “point of view” competing for recognition in the marketplace of ideas. Millions and millions of Americans regard it with an almost mystical reverence, regardless of what sort of social, political, or philosophical beliefs they may have. I cannot agree that the First Amendment invalidates the Act of Congress, and the laws of 48 of the 50 States, which make criminal the public burning of the flag.

More than 80 years ago, in Halter v. Nebraska, 205 U. S. 34 (1907), this Court upheld the constitutionality of a Nebraska statute that forbade the use of representations of the American flag for advertising purposes upon articles of merchandise. The Court there said:

“For that flag every true American has not simply an appreciation, but a deep affection. . . . Hence, it has often occurred that insults to a flag have been the cause of war, and indignities put upon it, in the presence of those who revere it, have often been resented and sometimes punished on the spot.” Id. at 41.

Only two Terms ago, in San Francisco Arts & Athletics, Inc. v. United States Olympic Committee, 483 U. S. 522 (1987), the Court held that Congress could grant exclusive use of the word “Olympic” to the United States Olympic Committee. The Court thought that this

“restrictio[n] on expressive speech properly [was] characterized as incidental to the primary congressional purpose of encouraging and rewarding the USOC’s activities.” Id. at 483 U. S. 536.

As the Court stated,

“when a word [or symbol] acquires value ‘as the result of organization and the expenditure of labor, skill, and money’ by an entity, that entity constitutionally may obtain a limited property right in the word [or symbol].” Id. at 483 U. S. 532, quoting International News Service v. Associated Press, 248 U.S. 215, 248 U. S. 239 (1918).

Surely Congress or the States may recognize a similar interest in the flag. But the Court insists that the Texas statute prohibiting the public burning of the American flag infringes on respondent Johnson’s freedom of expression. Such freedom, of course, is not absolute. See Schenck v. United States, 249 U. S. 47 (1919). In Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568 (1942), a unanimous Court said:

“Allowing the broadest scope to the language and purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment, it is well understood that the right of free speech is not absolute at all times and under all circumstances. There are certain well defined and narrowly limited classes of speech, the prevention and punishment of which have never been thought to raise any Constitutional problem. These include the lewd and obscene, the profane, the libelous, and the insulting or ‘fighting’ words — those which, by their very utterance, inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace. It has been well observed that such utterances are no essential part of any exposition of ideas, and are of such slight social value as a step to truth that any benefit that may be derived from them is clearly outweighed by the social interest in order and morality.” Id. at 315 U. S. 571-572 (footnotes omitted).

The Court upheld Chaplinsky’s conviction under a state statute that made it unlawful to “address any offensive, derisive or annoying word to any person who is lawfully in any street or other public place.” Id. at 315 U. S. 569. Chaplinsky had told a local marshal, “You are a God damned racketeer” and a “damned Fascist and the whole government of Rochester are Fascists or agents of Fascists.” Ibid.

Here it may equally well be said that the public burning of the American flag by Johnson was no essential part of any exposition of ideas, and at the same time it had a tendency to incite a breach of the peace. Johnson was free to make any verbal denunciation of the flag that he wished; indeed, he was free to burn the flag in private. He could publicly burn other symbols of the Government or effigies of political leaders. He did lead a march through the streets of Dallas, and conducted a rally in front of the Dallas City Hall. He engaged in a “die-in” to protest nuclear weapons. He shouted out various slogans during the march, including: “Reagan, Mondale which will it be? Either one means World War III”; “Ronald Reagan, killer of the hour, Perfect example of U.S. power”; and “red, white and blue, we spit on you, you stand for plunder, you will go under.” Brief for Respondent 3. For none of these acts was he arrested or prosecuted; it was only when he proceeded to burn publicly an American flag stolen from its rightful owner that he violated the Texas statute.

The Court could not, and did not, say that Chaplinsky’s utterances were not expressive phrases — they clearly and succinctly conveyed an extremely low opinion of the addressee. The same may be said of Johnson’s public burning of the flag in this case; it obviously did convey Johnson’s bitter dislike of his country. But his act, like Chaplinsky’s provocative words, conveyed nothing that could not have been conveyed and was not conveyed just as forcefully in a dozen different ways. As with “fighting words,” so with flag burning, for purposes of the First Amendment: It is

“no essential part of any exposition of ideas, and [is] of such slight social value as a step to truth that any benefit that may be derived from [it] is clearly outweighed”

by the public interest in avoiding a probable breach of the peace. The highest courts of several States have upheld state statutes prohibiting the public burning of the flag on the grounds that it is so inherently inflammatory that it may cause a breach of public order. See, e.g., State v. Royal, 113 N. H. 224, 229, 305 A.2d 676, 680 (1973); State v. Waterman, 190 N.W.2d 809, 811-812 (Iowa 1971); see also State v. Mitchell, 32 Ohio App.2d 16, 30, 288 N.E.2d 216, 226 (1972).

The result of the Texas statute is obviously to deny one in Johnson’s frame of mind one of many means of “symbolic speech.” Far from being a case of “one picture being worth a thousand words,” flag burning is the equivalent of an inarticulate grunt or roar that, it seems fair to say, is most likely to be indulged in not to express any particular idea, but to antagonize others. Only five years ago we said in City Council of Los Angeles v. Taxpayers for Vincent, 466 U. S. 789, 466 U. S. 812 (1984), that “the First Amendment does not guarantee the right to employ every conceivable method of communication at all times and in all places.” The Texas statute deprived Johnson of only one rather inarticulate symbolic form of protest — a form of protest that was profoundly offensive to many — and left him with a full panoply of other symbols and every conceivable form of verbal expression to express his deep disapproval of national policy. Thus, in no way can it be said that Texas is punishing him because his hearers — or any other group of people — were profoundly opposed to the message that he sought to convey. Such opposition is no proper basis for restricting speech or expression under the First Amendment. It was Johnson’s use of this particular symbol, and not the idea that he sought to convey by it or by his many other expressions, for which he was punished.

Our prior cases dealing with flag desecration statutes have left open the question that the Court resolves today. In Street v. New York, 394 U. S. 576, 394 U. S. 579 (1969), the defendant burned a flag in the street, shouting “We don’t need no damned flag” and, “[i]f they let that happen to Meredith, we don’t need an American flag.” The Court ruled that since the defendant might have been convicted solely on the basis of his words, the conviction could not stand, but it expressly reserved the question whether a defendant could constitutionally be convicted for burning the flag. Id. at 394 U. S. 581.

Chief Justice Warren, in dissent, stated:

“I believe that the States and Federal Government do have the power to protect the flag from acts of desecration and disgrace. . . . [I]t is difficult for me to imagine that, had the Court faced this issue, it would have concluded otherwise.” Id. at 394 U. S. 605.

Justices Black and Fortas also expressed their personal view that a prohibition on flag burning did not violate the Constitution. See id. at 394 U. S. 610 (Black, J., dissenting) (“It passes my belief that anything in the Federal Constitution bars a State from making the deliberate burning of the American Flag an offense”); id. at 394 U. S. 615-617 (Fortas, J., dissenting) (“[T]he States and the Federal Government have the power to protect the flag from acts of desecration committed in public. . . . [T]he flag is a special kind of personality. Its use is traditionally and universally subject to special rules and regulation. . . . A person may own’ a flag, but ownership is subject to special burdens and responsibilities. A flag may be property, in a sense; but it is property burdened with peculiar obligations and restrictions. Certainly . . . these special conditions are not per se arbitrary or beyond governmental power under our Constitution”).

In Spence v. Washington, 418 U. S. 405 (1974), the Court reversed the conviction of a college student who displayed the flag with a peace symbol affixed to it by means of removable black tape from the window of his apartment. Unlike the instant case, there was no risk of a breach of the peace, no one other than the arresting officers saw the flag, and the defendant owned the flag in question. The Court concluded that the student’s conduct was protected under the First Amendment, because

“no interest the State may have in preserving the physical integrity of a privately owned flag was significantly impaired on these facts.” Id. at 418 U. S. 415.

The Court was careful to note, however, that the defendant “was not charged under the desecration statute, nor did he permanently disfigure the flag or destroy it.” Ibid.

In another related case, Smith v. Goguen, 415 U. S. 566 (1974), the appellee, who wore a small flag on the seat of his trousers, was convicted under a Massachusetts flag misuse statute that subjected to criminal liability anyone who publicly. . . treats contemptuously the flag of the United States.” Id. at 415 U. S. 568-569. The Court affirmed the lower court’s reversal of appellee’s conviction, because the phrase “treats contemptuously” was unconstitutionally broad and vague. Id. at 415 U. S. 576. The Court was again careful to point out that

“[c]ertainly nothing prevents a legislature from defining with substantial specificity what constitutes forbidden treatment of United States flags.” Id. at 415 U. S. 581-582.

See also id. at 415 U. S. 587 (WHITE, J., concurring in judgment) (“The flag is a national property, and the Nation may regulate those who would make, imitate, sell, possess, or use it. I would not question those statutes which proscribe mutilation, defacement, or burning of the flag or which otherwise protect its physical integrity, without regard to whether such conduct might provoke violence. . . . There would seem to be little question about the power of Congress to forbid the mutilation of the Lincoln Memorial. . . . The flag is itself a monument, subject to similar protection”); id. at 415 U. S. 591 (BLACKMUN, J., dissenting) (“Goguen’s punishment was constitutionally permissible for harming the physical integrity of the flag by wearing it affixed to the seat of his pants”).

But the Court today will have none of this. The uniquely deep awe and respect for our flag felt by virtually all of us are bundled off under the rubric of “designated symbols,” ante at 491 U. S. 417, that the First Amendment prohibits the government from “establishing.” But the government has not “established” this feeling; 200 years of history have done that. The government is simply recognizing as a fact the profound regard for the American flag created by that history when it enacts statutes prohibiting the disrespectful public burning of the flag.

The Court concludes its opinion with a regrettably patronizing civics lecture, presumably addressed to the Members of both Houses of Congress, the members of the 48 state legislatures that enacted prohibitions against flag burning, and the troops fighting under that flag in Vietnam who objected to its being burned:

“The way to preserve the flag’s special role is not to punish those who feel differently about these matters. It is to persuade them that they are wrong.” Ante at 491 U. S. 419.

The Court’s role as the final expositor of the Constitution is well established, but its role as a platonic guardian admonishing those responsible to public opinion as if they were truant schoolchildren has no similar place in our system of government. The cry of “no taxation without representation” animated those who revolted against the English Crown to found our Nation — the idea that those who submitted to government should have some say as to what kind of laws would be passed. Surely one of the high purposes of a democratic society is to legislate against conduct that is regarded as evil and profoundly offensive to the majority of people — whether it be murder, embezzlement, pollution, or flagburning.

Our Constitution wisely places limits on powers of legislative majorities to act, but the declaration of such limits by this Court “is, at all times, a question of much delicacy, which ought seldom, if ever, to be decided in the affirmative, in a doubtful case.” Fletcher v. Peck, 6 Cranch 87, 10 U. S. 128 (1810) (Marshall, C.J.). Uncritical extension of constitutional protection to the burning of the flag risks the frustration of the very purpose for which organized governments are instituted. The Court decides that the American flag is just another symbol, about which not only must opinions pro and con be tolerated, but for which the most minimal public respect may not be enjoined. The government may conscript men into the Armed Forces where they must fight and perhaps die for the flag, but the government may not prohibit the public burning of the banner under which they fight. I would uphold the Texas statute as applied in this case. [Footnote 2/2]

[Footnote 2/1]

[This footnote cited each of the 48 state codes which make criminal the public burning of the flag. See complete opinion here.]

[Footnote 2/2]

In holding that the Texas statute as applied to Johnson violates the First Amendment, the Court does not consider Johnson’s claims that the statute is unconstitutionally vague or overbroad. Brief for Respondent 24-30. I think those claims are without merit. In New York State Club Assn. v. City of New York, 487 U. S. 1, 487 U. S. 11 (1988), we stated that a facial challenge is only proper under the First Amendment when a statute can never be applied in a permissible manner or when, even if it may be validly applied to a particular defendant, it is so broad as to reach the protected speech of third parties. While Tex.Penal Code Ann. § 42.09 (1989)

“may not satisfy those intent on finding fault at any cost, [it is] set out in terms that the ordinary person exercising ordinary common sense can sufficiently understand and comply with.” CSC Letter Carriers, 413 U. S. 548 413 U. S. 579 (1973).

By defining “desecrate” as “deface,” “damage” or otherwise “physically mistreat” in a manner that the actor knows will “seriously offend” others, § 42.09 only prohibits flagrant acts of physical abuse and destruction of the flag of the sort at issue here — soaking a flag with lighter fluid and igniting it in public — and not any of the examples of improper flag etiquette cited in respondent’s brief.

JUSTICE STEVENS, dissenting.

As the Court analyzes this case, it presents the question whether the State of Texas, or indeed the Federal Government, has the power to prohibit the public desecration of the American flag. The question is unique. In my judgment, rules that apply to a host of other symbols, such as state flags, armbands, or various privately promoted emblems of political or commercial identity, are not necessarily controlling. Even if flagburning could be considered just another species of symbolic speech under the logical application of the rules that the Court has developed in its interpretation of the First Amendment in other contexts, this case has an intangible dimension that makes those rules inapplicable.

A country’s flag is a symbol of more than “nationhood and national unity.” Ante at 491 U. S. 407, 491 U. S. 410, 491 U. S. 413, and n. 9, 491 U. S. 417, 491 U. S. 420. It also signifies the ideas that characterize the society that has chosen that emblem as well as the special history that has animated the growth and power of those ideas. The fleurs-de-lis and the tricolor both symbolized “nationhood and national unity,” but they had vastly different meanings. The message conveyed by some flags — the swastika, for example — may survive long after it has outlived its usefulness as a symbol of regimented unity in a particular nation.

So it is with the American flag. It is more than a proud symbol of the courage, the determination, and the gifts of nature that transformed 13 fledgling Colonies into a world power. It is a symbol of freedom, of equal opportunity, of religious tolerance, and of goodwill for other peoples who share our aspirations. The symbol carries its message to dissidents both at home and abroad who may have no interest at all in our national unity or survival.

The value of the flag as a symbol cannot be measured. Even so, I have no doubt that the interest in preserving that value for the future is both significant and legitimate. Conceivably, that value will be enhanced by the Court’s conclusion that our national commitment to free expression is so strong that even the United States, as ultimate guarantor of that freedom, is without power to prohibit the desecration of its unique symbol. But I am unpersuaded. The creation of a federal right to post bulletin boards and graffiti on the Washington Monument might enlarge the market for free expression, but at a cost I would not pay. Similarly, in my considered judgment, sanctioning the public desecration of the flag will tarnish its value — both for those who cherish the ideas for which it waves and for those who desire to don the robes of martyrdom by burning it. That tarnish is not justified by the trivial burden on free expression occasioned by requiring that an available, alternative mode of expression — including uttering words critical of the flag, see Street v. New York, 394 U. S. 576 (1969) — be employed.

It is appropriate to emphasize certain propositions that are not implicated by this case. The statutory prohibition of flag desecration does not

“prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.” West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U. S. 624, 319 U. S. 642 (1943).

The statute does not compel any conduct or any profession of respect for any idea or any symbol.

Nor does the statute violate “the government’s paramount obligation of neutrality in its regulation of protected communication.” Young v. American Mini Theatres, Inc., 427 U. S. 50, 427 U. S. 70 (1976) (plurality opinion). The content of respondent’s message has no relevance whatsoever to the case. The concept of “desecration” does not turn on the substance of the message the actor intends to convey, but rather on whether those who view the act will take serious offense. Accordingly, one intending to convey a message of respect for the flag by burning it in a public square might nonetheless be guilty of desecration if he knows that others — perhaps simply because they misperceive the intended message — will be seriously offended. Indeed, even if the actor knows that all possible witnesses will understand that he intends to send a message of respect, he might still be guilty of desecration if he also knows that this understanding does not lessen the offense taken by some of those witnesses. Thus, this is not a case in which the fact that “it is the speaker’s opinion that gives offense” provides a special “reason for according it constitutional protection,” FCC v. Pacifica Foundation, 438 U. S. 726, 438 U. S. 745 (1978) (plurality opinion). The case has nothing to do with “disagreeable ideas,” see ante at 491 U. S. 409. It involves disagreeable conduct that, in my opinion, diminishes the value of an important national asset.

The Court is therefore quite wrong in blandly asserting that respondent

“was prosecuted for his expression of dissatisfaction with the policies of this country, expression situated at the core of our First Amendment values.” Ante at 491 U. S. 411.

Respondent was prosecuted because of the method he chose to express his dissatisfaction with those policies. Had he chosen to spraypaint — or perhaps convey with a motion picture projector — his message of dissatisfaction on the facade of the Lincoln Memorial, there would be no question about the power of the Government to prohibit his means of expression. The prohibition would be supported by the legitimate interest in preserving the quality of an important national asset. Though the asset at stake in this case is intangible, given its unique value, the same interest supports a prohibition on the desecration of the American flag. *

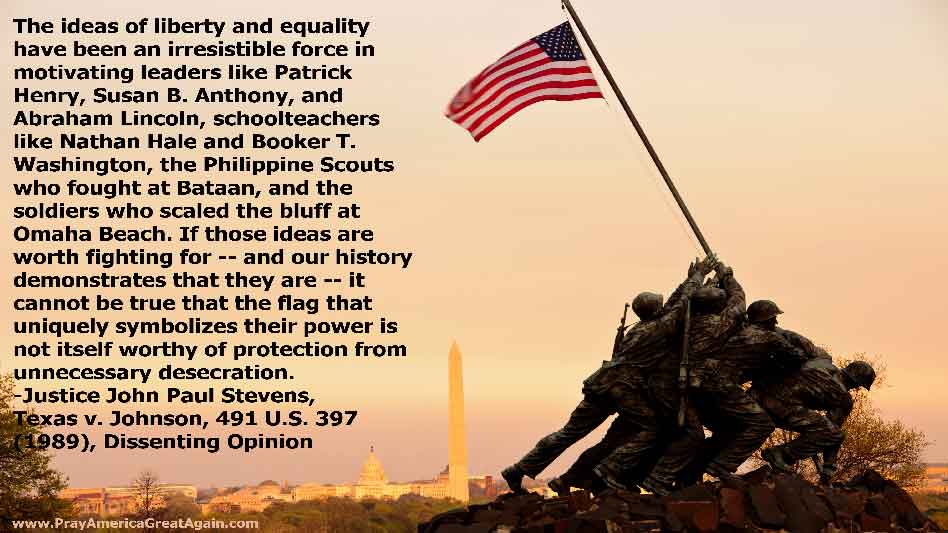

The ideas of liberty and equality have been an irresistible force in motivating leaders like Patrick Henry, Susan B. Anthony, and Abraham Lincoln, schoolteachers like Nathan Hale and Booker T. Washington, the Philippine Scouts who fought at Bataan, and the soldiers who scaled the bluff at Omaha Beach. If those ideas are worth fighting for — and our history demonstrates that they are — it cannot be true that the flag that uniquely symbolizes their power is not itself worthy of protection from unnecessary desecration.

I respectfully dissent.

* The Court suggests that a prohibition against flag desecration is not content-neutral, because this form of symbolic speech is only used by persons who are critical of the flag or the ideas it represents. In making this suggestion, the Court does not pause to consider the far-reaching consequences of its introduction of disparate-impact analysis into our First Amendment jurisprudence. It seems obvious that a prohibition against the desecration of a gravesite is content-neutral even if it denies some protesters the right to make a symbolic statement by extinguishing the flame in Arlington Cemetery where John F. Kennedy is buried while permitting others to salute the flame by bowing their heads. Few would doubt that a protester who extinguishes the flame has desecrated the gravesite, regardless of whether he prefaces that act with a speech explaining that his purpose is to express deep admiration or unmitigated scorn for the late President. Likewise, few would claim that the protester who bows his head has desecrated the gravesite, even if he makes clear that his purpose is to show disrespect. In such a case, as in a flag burning case, the prohibition against desecration has absolutely nothing to do with the content of the message that the symbolic speech is intended to convey.

Find Out More About Texas v. Johnson

Watch a Hillsdale lecture on this case.

PAGA article Texas v. Johnson and Congressional legislation (to be posted soon)

Read about the creation of the “O’Brien test” from U.S. v. O’Brien (1968) that aided the court to come to their conclusion in Texas v. Johnson (1989).